Maria Rye, and Her British Home Children

From the blog at http://JohnWood1946.wordpress.com

Now in Twitter @JohnWoodTweets

Maria Rye, and Her British Home Children

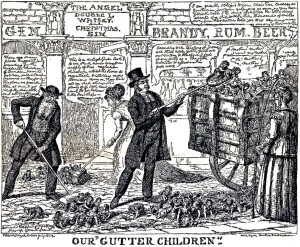

Loading Waste, Our Gutter Children

A satirical cartoon by George Cruikshank, from BritishHomeChild.com

Most people know that pauper and orphaned and stray children were imported into Canada from Britain in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. These were the ‘home children’, and they are remembered today for having been received into an unsatisfactory system. In too many cases they became unpaid labourers, and their circumstances in many other cases were not what we would call ‘adoption.’

An earlier blog posting about Elizabeth (Smith) Secord revealed, for example, that a shipment of children arrived from Britain in 1908 aboard the SS Carthaginian. These were ‘Middlemore Children’, imported by John Middlemore, some of more than 5,000 children extracted from Birmingham to separate them from their ‘bad companions’. Elizabeth took two of these children, and they were still with her by the time of the 1911 census. They were Herbert Morris born in 1895, and Elsie May Morris born in 1897. I do not know what happened to the Morrises. I can only hope that my relative, Elizabeth, treated them well. Elizabeth was New Brunswick’s first registered female medical doctor.

This blog posting is about an earlier similar program operated by a Maria Rye and Annie Macpherson in the 1870’s. Rye and Macpherson operated mostly in Ontario and Quebec, but also placed children in New Brunswick and in the newly opening West. Maria Rye received more attention in New Brunswick than did Annie Macpherson, and so I assume that she was the principal operator here. Maria was financed by subscriptions, and by payments by Guardians, and by Government grants.

Maria Rye was a British activist in the women’s movement, with a particular interest in improving the possibilities for single women to support themselves economically. By the late 1860’s, she was transporting women from Britain to the former colonies, including 200 to locations on the Saint Lawrence River. This aroused some controversy in Canada, so that in 1869 she changed her program to concentrate on poorhouse and orphaned children, mostly girls. Rye was not evangelical, but she still saw herself as a missionary, rescuing children from ‘evil’ and desperate circumstances in Britain and offering them better lives in Canada. Their circumstances were, in fact, quite desperate, as Charles Dickens had chronicled not so long before.

The testimonials that were written in defense of Maria Rye when her program was drawn into question show that she had a lot of influential friends who regarded her work favorably. I suppose, then, that she was sincere in her desire to help the hopeless. On the other hand, she and Annie Macpherson were, by necessity, limited in the amount of oversight that they could give to the many children that they imported. At the same time, there was no government oversight, no child welfare departments, and no uniform standards of care by which she could be judged.

There were three ‘classes’ of children brought to Canada. The first class, or group, were pauper children, collected from poor-houses and sent before Magistrates where they would be asked to consent to being sent abroad. The second class were orphans, and the third were a collection of others including waifs and strays, so called gutter children or ‘Arabs’, and children from reformatories. Only the paupers were examined by Magistrates and all of the others were exported on the authority of local functionaries. These authorizations were issued in such a casual way that it was impossible to confirm how or if they had been obtained. In Canada, Rye and Macpherson were assumed to have all of the necessary authorizations and were granted parental rights over the children.

Questions began to arise in Britain and, in 1874, British authorities commissioned Local Government Inspector Andrew Doyle in investigate and prepare a report. He visited a group of 150 children as they were being collected at port in Britain and also travelled to Canada to investigate here. His report was submitted in December of 1874, and published in February of 1875.

Having been collected at port, they were placed in group-homes or dormitories, to be shipped to Canada as quickly as possible where they could adopt more virtuous ways. One shipment was followed to Quebec City, from which the children were split up to other group-homes or dormitories awaiting distribution to families. Doyle visited about 400 of these children in holding facilities.

Applications to take children into families were then received. It is said that Rye reviewed and visited every applicant before accepting any of them, but the numbers were so large that this may not have been possible. In any case, each application was supported by a recommendation from an upstanding citizen and this was seen as quite a failsafe system.

Only the youngest of children were adopted in the usual sense and brought up as full members of their new families. Most others were placed according to ‘indentures of adoption’, which were apprenticeships. Some were found in remote cabins far from any community other than their adopters. Those in cities and towns, especially girls, were usually placed ‘in service’, having had no training for their new roles. When they grew to adulthood and were released they found themselves without trades and without any way of supporting themselves. Doyle had predicted, and it turned out to be true, that street children and others from reformatories were unlikely to readily convert to lives of virtue and ‘service’. He had recommended that no such placements be made until the children had been put through training that would give them a ‘trade’ of sorts.

Other evidence that these were not ordinary adoptions came from the testimony of one girl, who said “’Doption, Sir, is when folks gets a girl to work without wages.” There was also evidence of cruelty when another girl was discovered to have been “kept in solitary confinement for eleven days on bread and water as a punishment for having given way to a bad temper.” The collection system and their classification into paupers, orphans, ‘gutter children’ and inmates from reformatories was also found to be flawed, when one ‘orphan’ was found who did, in fact, have living parents in Britain.

About 1,150 children had been sent to Canada by the time of the Doyle Report, aged from infants to 14 or 15 years. The program was still in progress as the report was being written, and more were on their way.

No sooner had the report been issued than it became a topic in the press. The Liverpool Mercury, the Manchester Evening News, the Birmingham Daily Post and the Freeman’s Journal all ran articles and, of course, the news soon spread to Canada.

Many people, including Leonard Tilley and Lemuel Wilmot, wrote letters of support once the Doyle Report had become public. Many of the letters were pro forma, but John Boyd’s letter from Saint John was more revealing. Boyd was a businessman and politician, and would become a Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick. He wrote a spirited defense of Maria Rye, and accused Doyle of being maliciously unfair. Many children turn out badly even in the best of families, he said, and the fact that some of the British girls had ‘fallen’ and a couple of others had become ‘bye words’ was no fault of Rye. Boyd had served as a ‘Guardian’, to whom a couple of adopted children could turn if they had any problems, there were few complaints, however, aside from a girl who had had “a drunken master, [and was given] permission to leave and go to another home”. Besides, children were apt to complain, and visitations to the homes would not have been useful and would only have been viewed as government ‘inquisitions’. Overall, Boyd’s letter was overly dismissive.

Rye had hoped that local governments would eventually take over the oversight of the children, but the Doyle report had raised controversy and this never happened. Rye retired in 1895 and left the care of her children in Ontario to a Church of England Society. I do not know if there were still any children in care in New Brunswick at that time.

References:

- Further letters furnished to the Department of Agriculture by Miss Rye, in rebuttal of Mr. Doyle’s report, 1875. From the collections of the Public Archives of Canada. At https://archive.org/details/cihm_23997

- British Home Children in Canada, The Doyle Report on Pauper Children in Canada, February, 1875, at http://canadianbritishhomechildren.weebly.com/the-doyle-report-1875.html

- Joy Parr, Maria Susan Rye, in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- John Wood, Elizabeth (Smith) Secord; First Registered Woman Doctor in N.B., in this blog at https://johnwood1946.wordpress.com/2011/11/04/elizabeth-smith-secord-first-registered-woman-doctor-in-n-b/

Leave a comment